No sooner than there is news about the Central Bank of Sri Lanka printing money, images of people carting off money in wheelbarrows in Zimbabwe flood the popular media. Zimbabwe, a country that has earned a reputation for money printing and hyperinflation, is used as “evidence” to tie the two phenomena together as one causing the other. In other words, the theoretical premise that money printing causes inflation is touted by many as if it is an absolute truth. This is because there is selective amnesia about the objective conditions in Zimbabwe that led up to the hyperinflation crisis.

Economics textbooks explain how money printing causes inflation to rise. This is done using Irving Fisher’s Quantity Theory of Money (QTM) equation: M*V = P*T

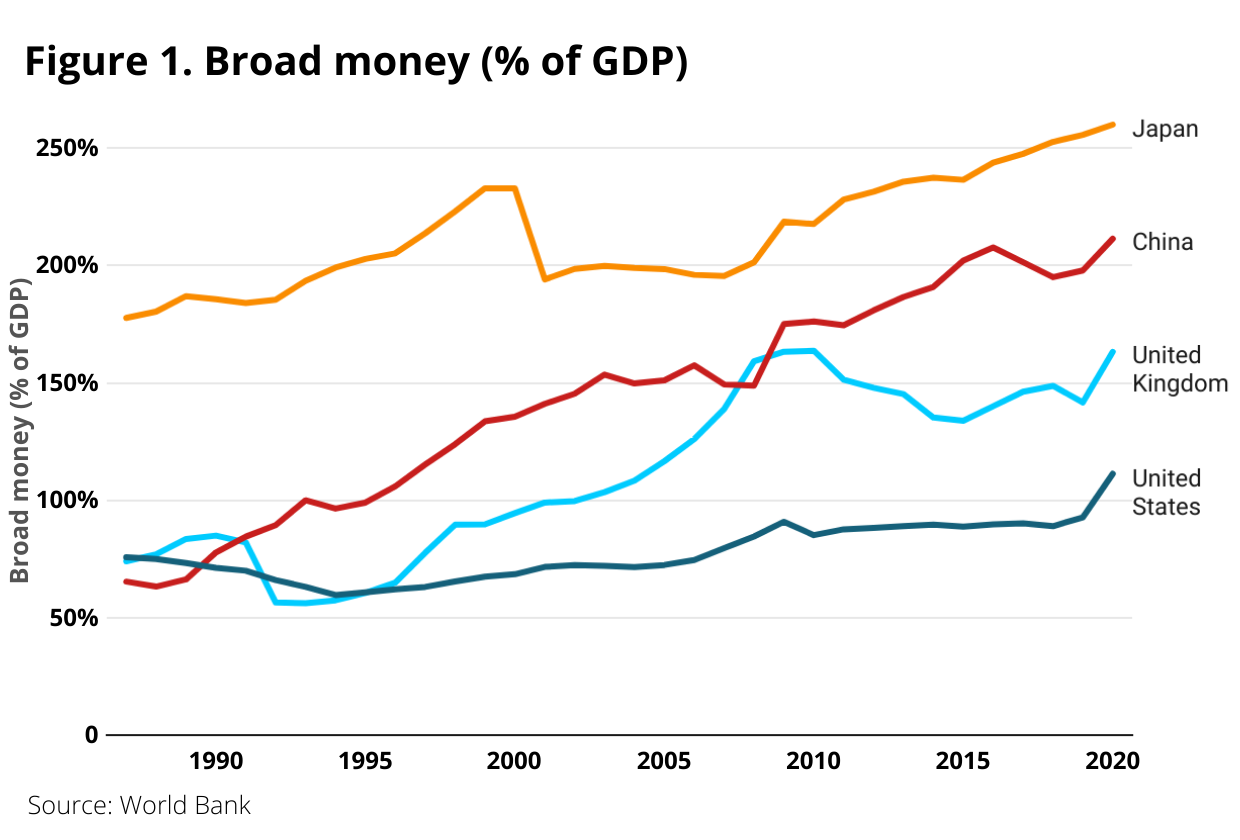

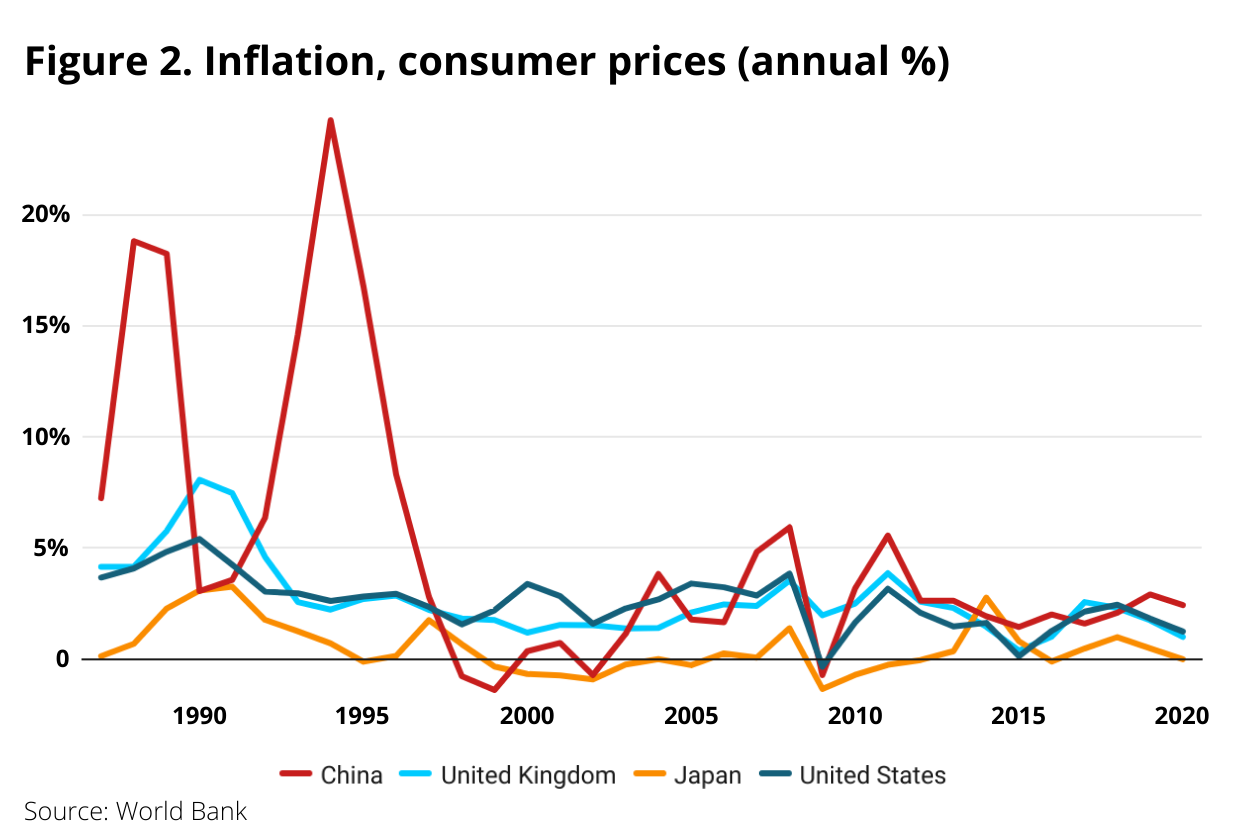

The theory makes the assumptions that velocity of money (V) and the output (T) will remain constant in the short term. As a result, any increase in money supply (M) will directly result in the price (P) to rise. This may be an easy and simple way to explain inflation, but many real world cases have proved that this does not hold. For example, a simple comparison of Japan’s money supply compared with its inflation (even deflation) data will show that the theory fails. If that does not suffice, countries like China, the US, and the UK have all been experiencing low levels of inflation with high growth in money supply. This is because these countries have utilised the excess money supply towards production, allowing them to increase output ahead of demand. They have maintained low levels of inflation with high levels of money supply (Figure 1 and 2).

Zimbabwe’s side of the story

Zimbabwe’s inflation skyrocketed in 2007-2008, while large sums of money were printed by the state. However, a deeper look into what really happened in Zimbabwe will show the underlying factors at play which caused hyperinflation.

First, some context: Zimbabwe gained independence from the British in 1980, which was followed by a period of prosperous growth. The economy grew at an average GDP growth rate of 4.3% a year between 1980 and 1998, under the rule of Robert Mugabe, the first prime minister of independent Zimbabwe. However, by the end of the 1990s, the country’s economic progress came to a halt as the country entered into a depression.

As the disparity between the Black Zimbabweans and the land-owning White community began to widen, Black Zimbabweans turned against the governing regime. At the same time, the war veterans loyal to the ruling party started demanding for a larger stake and more compensation. This put the Mugabe government under stress, as it had to secure its popularity among influential war veterans and the majority population of the country. In response, the Mugabe government increased pension payments and gave other forms of benefits to veterans. In 1998, the Mugabe government deployed the Zimbabwean military to support the Laurent Kabila government in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Both the pensions and military wages were financed through printing money.

A forgotten supply side disruption

Uprisings of Black Zimbabweans against the White land-owners pressurised the ZANU-PF government, led by Robert Mugabe, to start enforcing land reforms in the mid-1990s. In early 2001, war veterans mobilised Black Zimbabweans to march on White-owned farmlands and take them over. The state did not intervene to stop this mass seizure of land, but supported it.

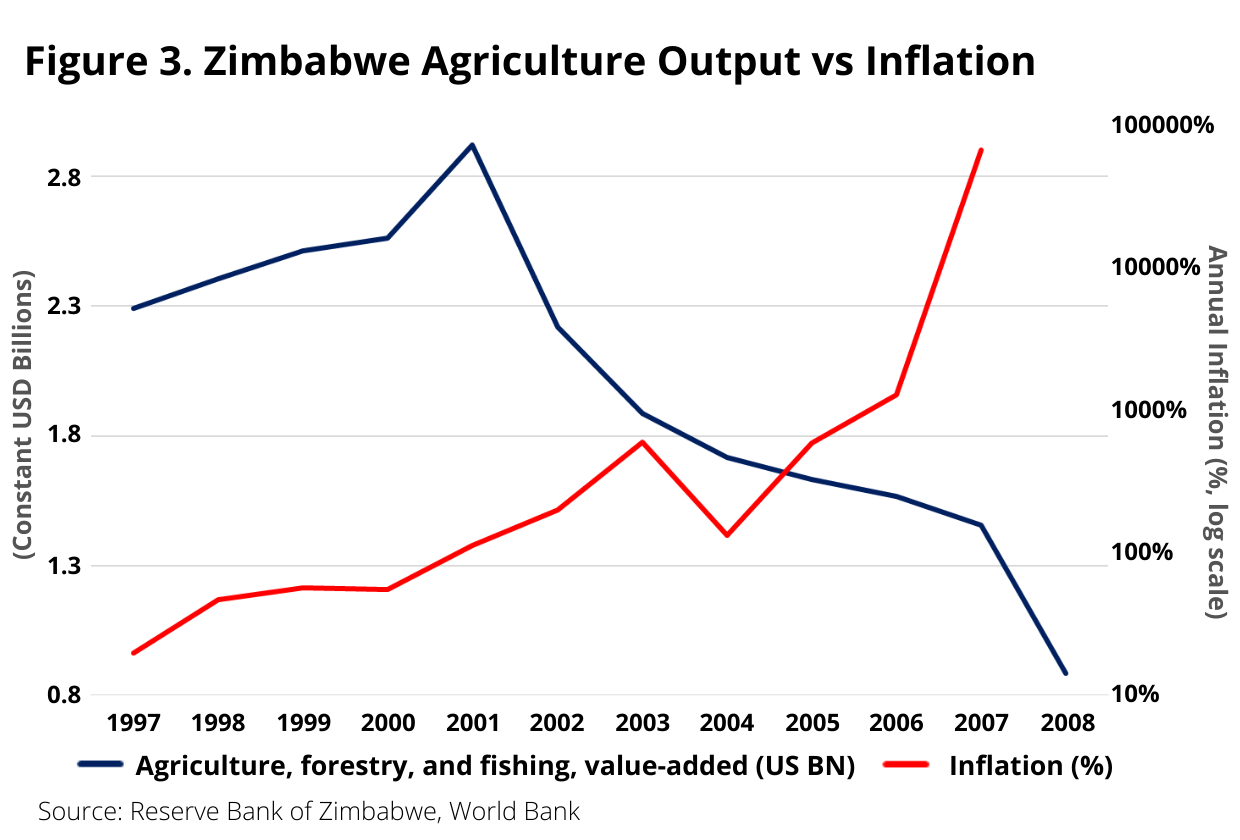

Figure 3 depicts Zimbabwe’s agriculture, forestry, and fishing output between 1997 and 2008. A clear drop in agricultural output can be observed between 2002 and 2008, due to the sudden switch in management from commercial White farmers to Black Zimbabweans who were inexperienced in commercial agriculture. Further to that, banks did not finance these farms as there was no clear asset ownership to be placed as collateral. The agricultural output declined at an annual average of 15% over the seven years from $ 2.9 billion in 2001 to a low of $ 0.8 billion in 2008. Zimbabwe, being an agricultural exporter (mainly tobacco leaf), lost out on a large foreign exchange inflow, which resulted in the currency depreciating over time. Due to the shortage in food supply, food had to be imported. The combination of the two factors caused prices to rise. The Mugabe government addressed this problem by printing money to finance consumption in Zimbabwe and fight a war in the DRC, which in return devalued the currency and resulted in hyperinflation.

A production economy left behind

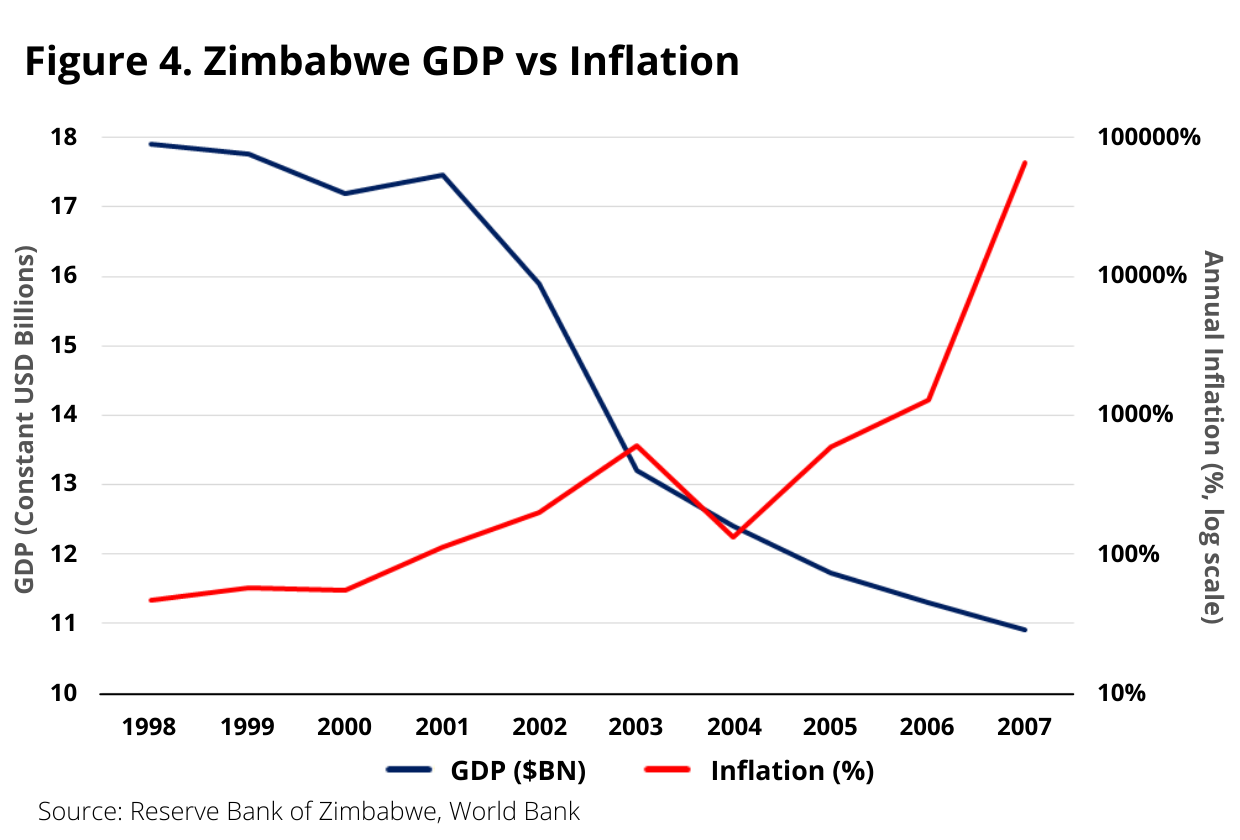

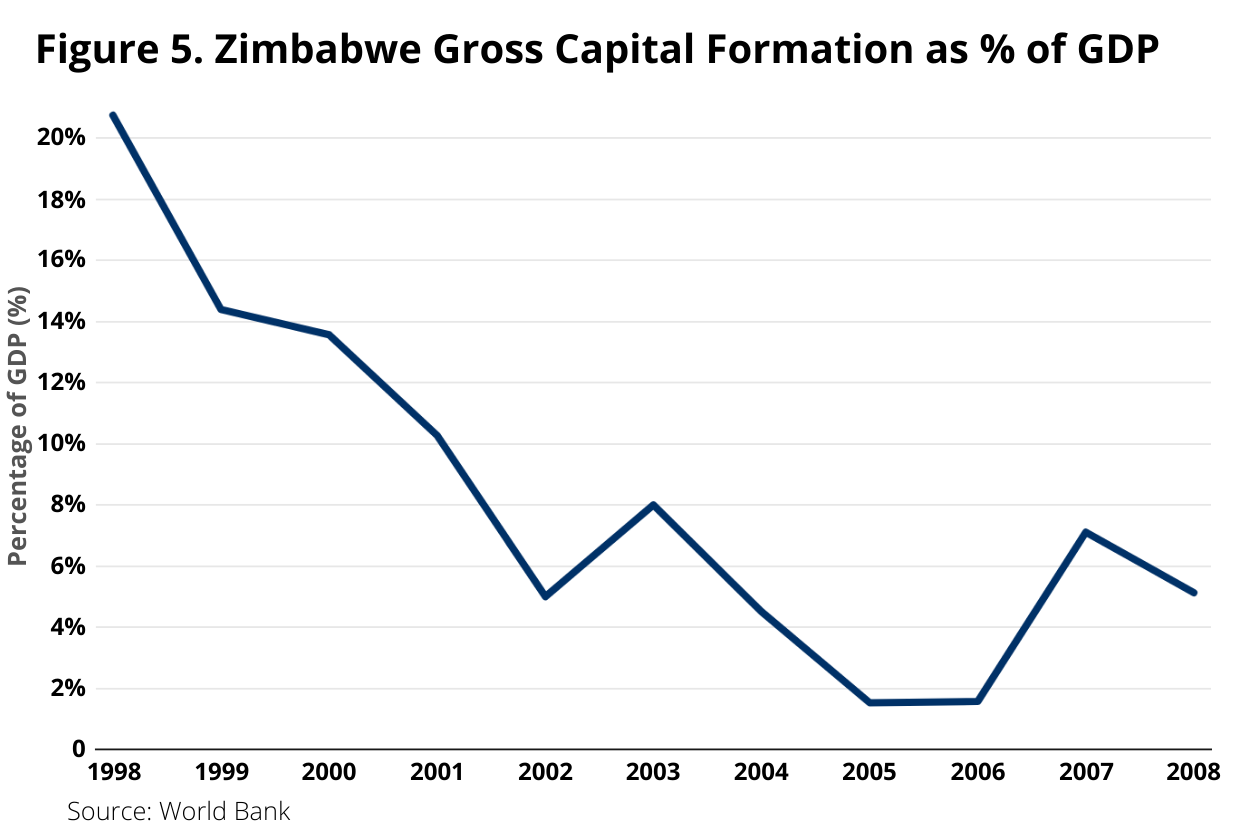

The Zimbabwe story does highlight that hyperinflation was made possible by printing money, however there were a few underlying causes that facilitated the crisis. Figure 4 compares gross domestic output of Zimbabwe against annual inflation rate, and the two have a negative correlation, emphasising that as output decreased, inflation rose. However, a comparison of broad money and inflation will show that as money printing increases, inflation has risen. It is important to identify where this printed money was used. The capital formation of Zimbabwe as a percentage of GDP (Figure 5) shows that the money printed was not used for capital investment into the economy. The rate of capital formation declined from 20% of GDP in 1998, to 1.5% of GDP in 2005. In contrast, Sri Lanka maintained an annual average capital formation of 25% of GDP between 1998 and 2005. It becomes clear by the decline in capital formation that there was a lack of investment into production in Zimbabwe leading up to 2008. The disruption in the agricultural sector, lack of investment into production, and the printing of money to finance consumption created the underlying setting for Zimbabwe to enter a hyperinflationary crisis which further disrupted the economy.

Is Sri Lanka the next Zimbabwe?

Sri Lanka is also printing money, and there is a lot of criticism surrounding this. But the key question is what the printed money is being used for. In the latter part of 2019, the state announced a looser fiscal policy by lowering taxes on businesses and investment. It also gave out many tax breaks for businesses to encourage expansion into global markets through exports. Such a measure reduces government tax income in the short run. However, the expectation that firms would set up production plants to expand output, taking advantage of the tax relief, was somewhat thwarted in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic, which in turn exacerbated the global economic slowdown that was already in motion.

The economic effects of the pandemic further reduced tax income, while also increasing public health expenditure. The decline in transactions of goods and services during the lockdown period resulted in the direct and indirect tax income to decline in 2020. This mismatch between government tax income and government expenditure has been financed by the printing of money to maintain the level of public spending needed for the country. This is the funding mechanism set in place in countries that run a budget deficit. It is good to remind ourselves that Sri Lanka has large public, health, education and energy sectors, which are cherished continuities of our welfare state. These sectors provide services at highly subsidised rates, and are able to do so because the state is able to maintain the funding for these institutions. Furthermore, the Central Bank has aligned the monetary policy with the country’s expansionary fiscal policy, mandating a single digit interest rate policy. Both the fiscal and monetary policy is in line to create an investment friendly, pro-production economy, while maintaining welfare provisions.

Sri Lanka has printed money to facilitate the expansion of production and capital formation by giving out tax breaks and tax incentives to firms. The printed money finances the public sector, providing businesses and people healthcare, education, electricity, water and even fuel at a subsidised rate. This has reduced the cost of living for people and lowered the cost of production for businesses, making Sri Lankan product prices competitive in the global market. The money printed has been used to incentivise production and expand output in the economy, which in return brings down inflationary pressure in the long run. In contrast, Zimbabwe used its printed money to fund consumption, through the pensions of its veterans and funding for its war efforts. Further, as a result of land seizure, the country experienced a sharp fall in its agricultural production. All three acts did not incentivise production, and the latter disrupted production. In conclusion, the underlying conditions of Sri Lanka’s money printing remain vastly different to the conditions obtained in Zimbabwe. Hence, comparing the two countries is grossly misleading, as one printed money for consumption and the other to finance a production economy with a strong welfare state.

(The writer is an Economic Research Analyst at Econsult Asia, which is an economic research and management consultancy firm with an alternative development outlook)

Post published in: Business