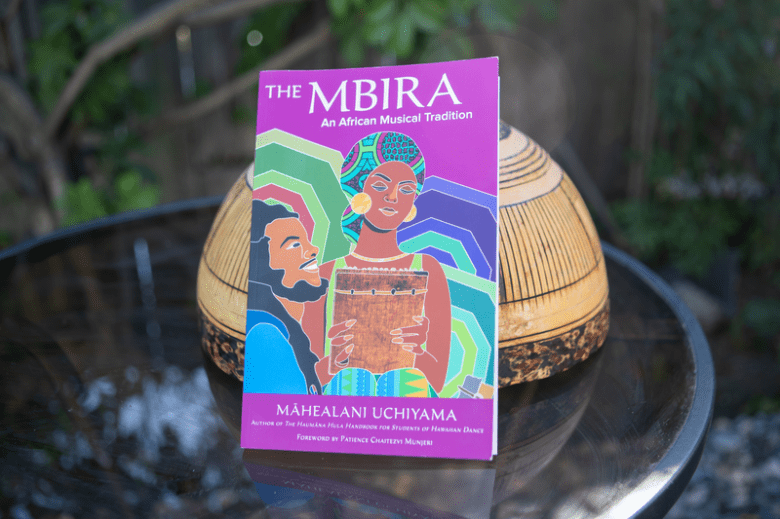

Dancer, musician, composer, and choreographer Māhealani Uchiyama, with an mbira, an instrument of the Shona people of Zimbabwe. Uchiyama’s new book, The Mbira: An African Musical Tradition, hits shelves Sept. 14. Credit: Amir AzizWhat started as an unplanned excursion to Berkeley’s Freight & Salvage for Māhealani Uchiyama turned into a life altering musical journey that she recounts in her new book, The Mbira: An African Musical Tradition.

It was the winter of 2001, and Uchiyama had already earned international recognition as a choreographer, dancer, musician and teacher, deeply immersed in hula, one of many traditions taught at the West Berkeley-based Mahea Uchiyama Center for International Dance, which she founded in 1993. But all her experience engaging with music from around the world didn’t prepare her for being swept up by the interlocking patterns played on mbira by Forward Kwenda and Erica Azim.

A traditional instrument consisting of a wooden soundboard with hammered metal keys, the mbira provided a portal to a spiritual plane where Uchiyama started “having visions, traveling to places, visiting relatives who’d passed away,” she recalled. “I got lost in their music in ways that I wasn’t expecting. It was a very powerful, personal experience. I signed up for lessons the next day.”

Uchiyama has spent the past two decades studying the sacred tradition of the Shona people with Azim and an array of Zimbabwean masters. (Full disclosure: Uchiyama and I serve on the board of Azim’s nonprofit organization MBIRA, which supports traditional Shona musicians and instrument makers in Zimbabwe).

The Mbira: An African Musical Tradition provides an introduction to the history and practice of mbira and its central role in Shona culture as a vehicle for healing and spiritual communion.

Referring both to the musical tradition and the wooden instrument with hammered metal keys, mbira can be played solo or in duet, and is often accompanied by singing, clapping, dancing, and percussion. While written for a general audience, Uchiyama’s book is also part of her ongoing effort to introduce mbira to African-American audiences. A weekly online course offered through the dance center has attracted a dozen Black students.

Most American descendants of slavery trace their African ancestry back to West Africa, at least 2,000 miles from Zimbabwe, but Uchiyama believes that engagement with an African heritage tradition, regardless of its geographic origins on the continent, is valuable.

“Even though there’s not the direct and obvious ancestral connection to southern Africa, there is still this sense we have been cut away from our heritage, deliberately discouraged and shamed out of pursuing any knowledge that would enrich us and place us in our power,” she said.

A grant from the Alliance for California Traditional Arts allowed Uchiyama to purchase new mbiras made by Salani Wamkanganise, a Shona musician and instrument maker who recently moved to Richmond from Zimbabwe’s capital, Harare. Each student in Uchiyama’s mbira class has one of Wamkanganise’s instruments at home.

Wamkanganise’s connection with mbira runs deep. A sickly child, he became smitten with mbira after he says a healing ceremony ended his persistent maladies. Over the years he’s performed widely around Zimbabwe, where he found his other calling as an instrument maker. Like many mbira musicians, he’s long been curious that most North Americans visiting Zimbabwe to study mbira are white. Now that he’s married to an American and living in the East Bay, he’s eager to work with Uchiyama to teach mbira to all sincerely interested people.

Her instrument, mbira, plays the sacred music of the Shona people of Zimbabwe (mbira is the primary instrument in the tradition)

An mbira, the primary instrument of the musical tradition of the same name. Credit: Amir Aziz

“Our traditional music is more community based, it involves everyone,” he said. “Back home, I don’t know racism. I just see human beings. I see souls. I just want to teach anyone who wants to learn. I don’t look at color or how rich you are. If your soul is open and loving you can receive the music.”

As an African-American woman who found her primary creative path in the Hawaiian tradition of hula, Uchiyama is versed in learning a sacred art form via relationships with indigenous practitioners. As co-artistic director of the San Francisco Ethnic Dance Festival since 2018, she’s been a binding force for elevating dance traditions from around the world in the Bay Area.

She says she didn’t set out to teach mbira herself, but she often felt isolated as the only Black person in mbira settings. A series of experiences led her to see that mbira’s predominately white following in North America created a dynamic that often minimizes African-American involvement.

She released her first mbira album, Ndoro dze Madzinza, in 2010 “not to say that I’m really great, but that I need to do this but because there was not enough of a presence of Black American people doing this music,” she said. “I wanted to make that statement: We’re here.”

For a variety of reasons, the Pacific Northwest has been the center of study for mbira since the late 1960s (when Zimbabwe was ruled by a white minority government and known as Rhodesia). Ever since Shona musicologist Abraham Dumisani Maraire landed in Seattle to teach at the University of Washington (and later Evergreen State College) the region has hosted a significant mbira scene, including the annual ZimFest since 1991. The relatively small Black population of the Pacific Northwest is reflected in the event’s demographics.

Uchiyama attended her first Zimfest in 2003, and was disappointed that some of the teachers were less than stellar. “It wasn’t that they weren’t Shona or of African descent, but it wasn’t well done,” she said. “I had been in a Caribbean/African dance company for a number of years and I could have taught that class. The following year I submitted an application to offer to teach, and it was turned down.”

Her first visit to Zimbabwe in 2007 cemented her connection with master musicians like Caution Shonha and Patience Chaitezvi Munjeri, a rare female mbira practitioner who wrote the foreword to her new book. Uchiyama has visited Africa before, spending time in Senegal, but during her time in Zimbabwe she felt “the spirits of ancestors were very close, playing that music with the people there, eating the food that was freshly prepared, breathing the air, slowing down. Sunsets became a thing.”

As one of only two people of African descent on the trip, she made an impact with her perspective. Months after she returned home, Uchiyama received an email from Patience Chaitezvi Munjeri’s brother Endiby Makope saying that her example provides “a rebuke” that led him “to return to the way of my forefathers.”

“While everyone else concentrated on the technical aspects of mbira music, you lived and operated on a higher plane–the spiritual. I watched you hold court with my ancestors, and without language, you took me down memory lane.”

Her book, The Mbira: An African Musical Tradition, which is being released on Sept. 14.

Māhealani Uchiyama’s new book is being released on Sept. 14. Credit: Amir Aziz

In 2013, Uchiyama released her second mbira album, The Sky That Covers Us All, and made her second Zimbabwean sojourn in 2016. The aftermath of that trip sparked her determination to write the book, as did an encounter with an ethnomusicologist who showed considerable ignorance about the tradition. Uchiyama said he argued that the “mbira is not a sacred instrument,” contradicting many of the Shona people’s own understanding.

“He said most sacred African music is played by drum and flute ensembles. He had no idea what he was talking about.”

Uchiyama is known for setting the record straight. Her 2016 volume The Haumana Hula Handbook for Students of Hawaiian Dance details the cultural and spiritual role of hula for the Hawaiian people and offers sensible methods for non-Hawaiians to study the tradition respectfully. Rather than positioning herself as a guardian or a gatekeeper, she sees her role as conduit between cultures, a Westerner mindful of ongoing colonial legacies.

“I have a duty to be an explainer, to connect different communities that are attracted to the same thing,” Uchiyama said. “For all of our material wealth, we’re so spiritually devolved. We have a lot to learn from a lot of these communities.”

Post published in: Entertainment