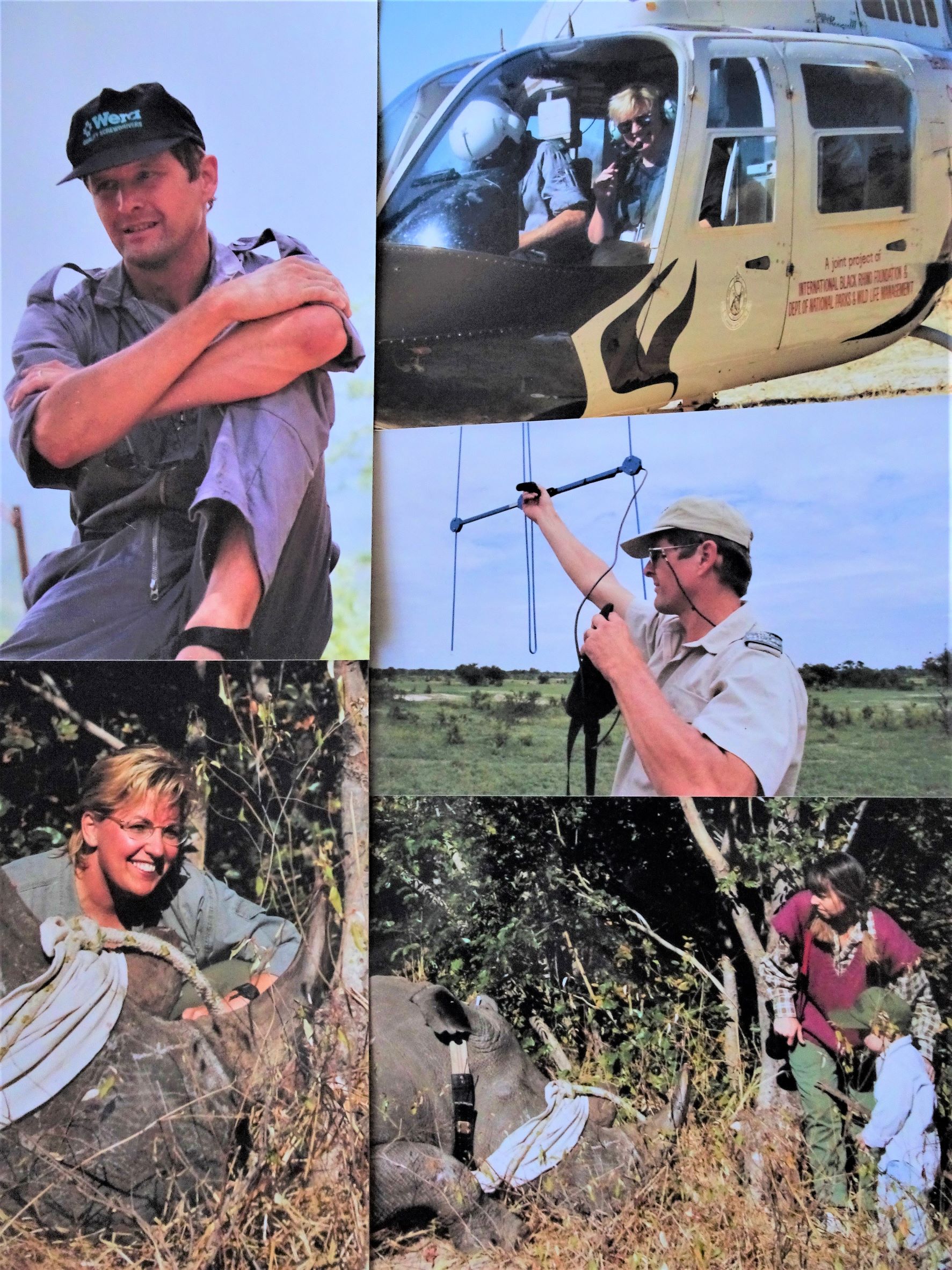

Images in accompanying photograph, in clockwise order – 1. Andy, in the year before his death. 2. I sometimes flew with Andy in the helicopter that eventually claimed his life. 3. While on frequent holidays to Hwange, I would also go out with Andy to track rhino and lion. 4. Lol and Drew beside a wild rhino (sedated from the helicopter flown by Andy) awaiting dehorning. 5. I’m with this same sedated rhino (in the late-1990s) inside Hwange National Park.

The month of March is, for me, always one of sad reflection… In my first South Africa-published book titled THE ELEPHANTS AND I, I wrote extensively about the death of my friend, Zimbabwean Andy Searle, in a chapter called ‘Life Changing Events’.

(Although this book – first published in 2009 – is out-of-print, I do eventually plan to put it up on Amazon as an Ebook, for just a couple of dollars to cover Amazon costs, given readers of my latest memoir ELEPHANT DAWN have been asking to read some of my earlier titles. Ebooks weren’t a thing – or at least not a big thing, especially in Africa – when ‘The Elephants and I’ was first published.) For now, I’m sharing here just a portion of this book chapter; my memories of those fateful days in March of the year 2000, which changed my life forever.

All these years later Andy, his wife Laurette (Lol), and their son Drew now in his 20s, remain forever close to my heart and are never far from my thoughts. My life and work with the Hwange elephants (2001-2014) – with the clan known as the Presidential Elephants of Zimbabwe – may never have happened without them. Andy’s untimely death on 6 March 2000 – one year before I arrived in Hwange to live – is something etched in my heart and soul forever.

The paragraphs below are from ‘The Elephants and I’ – in memory of a special human being who – despite some differing views – encouraged, and inspired, me to live and work amongst the Hwange elephants….

Andy, alone in the chopper, was dead.

Seated in an office block in Brisbane [Australia], I stared at my computer screen, reading and re-reading just this first line of the message.

‘It can’t be true,’ I whispered over and over.

Yet it was.

My decision to fly to Zimbabwe wasn’t a fully conscious one. I woke up two mornings after receiving the news, tired and miserable after another restless night, and knew that I had to get on a plane – even if it meant breaking my work contract. Already I felt that Andy’s death would somehow greatly impact my future life.

I never imagined that a trip to Africa could be so sad. Memories churned over in my mind, none bringing comfort. John and Del [Foster] were waiting at Victoria Falls airport to meet me, where tears replaced the usual joy. We reminisced a little during the two-hour drive to Hwange National Park, but mostly we tried to make sense of this tragic loss. Through the window I watched the countryside pass me by. The summer rains had been kind, but it no longer felt like the Zimbabwe that I loved.

We drove straight to the park’s Main Camp entrance, where the friendly boom-gate attendant who always remembered me was on duty. He beamed at me, a bright broad smile, before realising that I must have come to say goodbye to Warden Searle. His smile dissolved as he shook my hand in the triple movement African way, not letting it go for some time. The pain in my face transferred to his and he opened the boom-gate without asking any questions.

The road to Umtshibi seemed long. We stopped on the way to let Julia [Salnicki], who lived in a research cottage inside the park, know that I’d arrived. Our sombre greeting reflected our shock and disbelief. When we finally arrived at Umtshibi I sat quietly with Lol, knowing there was little I could say to comfort her.

I’d been offered accommodation at the rustic Miombo Lodge, by people [Val and Paul De Montille] I hadn’t met. United by grief, we were instantly friends. Exhausted after my long journey, I turned in early. I hadn’t slept properly for days, and now I was jetlagged as well. The elephants didn’t care though. They slurped and rumbled noisily beside the small waterhole just metres from my tree-lodge.

‘I have to get some sleep,’ I murmured to myself as I tossed and turned. Then I thought of Andy, and how he’d fully understood my love of the elephants. I couldn’t wish them away. He would never have believed it.

I forced myself out of bed at dawn and tried to prepare myself for the funeral of the person who’d enriched my feeling for Africa like no other. I went to Julia’s cottage and, from the surrounding bush, picked bright yellow daisy-like wildflowers for Andy’s grave.

It was a long, slow, silent drive along the railway line to where Andy was to be buried. I had travelled this same route with him the previous year while trying to find a snared zebra. I wondered what would happen to these injured animals now. Who would care enough to save them?

Andy was to be buried on the private land of ‘The Hide’ safari camp, bordering Hwange National Park. There are no fences here; it is home to Hwange’s wildlife. How appropriate for Andy to be laid to rest in the area he loved so much; in the land to which he belonged. From beneath the magnificent ebony tree where he was to be buried, he could still enjoy the animals in the sunset – those he had dedicated his life to saving.

Safari vehicles were everywhere. Perhaps two hundred people were already waiting. Julia, another friend and I walked, with heavy hearts, across a clearing of green grass towards the ebony tree. Sad, familiar faces acknowledged us as we passed beyond the tree and the freshly dug grave to where two tents had been put up as protection from the sun and possible rain. To our left were black faces, and white ones to our right, a separation that I noticed even in this time of grief. Without words, we joined our African friends on the left, and the separation melted away. Their singing and dancing brought more tears to my eyes. I sat on a wooden bench, holding on tightly to a small ceramic lion cub – bought in memory of the ‘family reunited’ adventure that Andy and I had shared.

Andy’s coffin arrived, carried by friends. We were outdoors under African skies without stained-glass windows, a thundering organ or even a priest. A member of Lol’s family led the service. After acknowledging the beautiful surroundings, an anecdote was shared. While helping to dig his grave the day before, one of Andy’s men was overheard saying, ‘What a fitting site for our chief.’ Many Umtshibi men and women were there, and Andy had indeed been their chief.

The service was an unforgettable tribute to an extraordinary man. Lol bravely shared many tales about the man she loved. When she talked about Andy’s men, she asked for an interpreter – to make sure that everyone understood. As she spoke, tears fell from the faces of those sitting all around me.

An invitation was then extended for others to say a few words. The tributes flowed from close friends and family. Although I hadn’t planned to say anything, I suddenly found myself side-stepping past my seated friends and walking up to the microphone. There I shared the fact that Andy was my hero. My own words tore at my heart as I struggled to convey how much I’d miss him.

Soon, people around me began singing ‘Rock of Ages’ while Andy’s scouts paid a final tribute, their rifles pointed skyward. Andy’s National Parks beret and belt were officially handed over to his grief-stricken parents. There was a final salute in honour of their son, and then the coffin was lowered.

Lol and Drew approached Andy’s open grave. Lol threw the first handful of soil onto the coffin while Drew, holding his mother’s hand, looked down in bewilderment. Eventually he took his own handful of soil and watched as it landed on his daddy’s coffin below.

I watched my own trembling hands reach out for some soil. ‘See you just now’ – Andy’s final words to me – I repeated to him, as I released my handful of earth.

Back at Miombo Lodge it seemed easier to stay awake than go to bed and face the night. I sat with a friend around a log fire, under the star-filled sky, talking and reminiscing. Unexpectedly, it began to rain. We could hear raindrops pelting the ground around us and could see them falling into the swimming pool, yet we weren’t getting wet. I guess there was a logical explanation, but it felt as though Andy was up there holding a huge umbrella over us, protecting us. We gazed at the sky and smiled.

I spent the next day driving alone in Hwange National Park. There was more rain – drops that would stimulate new life. Even so, the park felt empty and lonely. I knew it would never feel quite the same again. A piece of my Africa was gone forever.

I drove around until late in the afternoon, stopping to watch dung beetles roll their balls of elephant dung and families of guineafowl feeding. I was unhappy and confused. Out loud I asked Andy for a sign – something to let me know that everything was okay with him.

As I rounded the next bend in the road I caught my breath. It was one of the most beautiful sights I’d ever seen in Africa. The sun had peeped through the heavy clouds and more than 20 giraffes were mingling peacefully in this glorious twilight. I watched, mesmerised by their silent splendour. Soon a different, unforgettable, scene unfolded. A shaft of bright white light fell from under a huge cloud, towards a tree on the horizon. I was overawed by the heavenly look and feel, and found myself enveloped in warmth. I took one photograph and then it was gone. I had my sign.

I knew that I’d be late getting out of the park if I didn’t leave then. I was on my way when I came across 15 crowned cranes at the roadside – extraordinarily beautiful birds, with stunning grey plumage, bright red wattles and yellow crowns. Drawings of them had adorned Andy’s funeral service sheet. I accepted it, unquestioningly, as another sign.

During the days that followed, I spent time with Lol and other friends and then, when it was time for Lol to leave for Andy’s memorial service in Harare, I went to say goodbye to her at Umtshibi. As I drove away sadly in darkness, I suddenly found myself behind the enormous backside of a lone bull elephant. Forced to travel at his chosen speed, the drive took me twice as long as it should have. I didn’t mind though, for I derived great pleasure and comfort from his lingering presence. Later, Lol thoughtfully referred to this elephant encounter as having been ‘a gift from Andrew’.

My visit had turned into a week of extra-special memories that I knew I’d hold close to my heart forever.

Back in Australia I re-read an e-mail Andy had sent me two weeks before he died. I hadn’t replied to it. It was short, as they always were.

‘See you in July?’ he’d written.

July was just a few months away. I thought it might be too painful to go back so soon after his death. Once the memories became comforting and could bring a smile, I would return.

Ties with my ‘African family’ had been strengthened, although those of us who loved Andy would never be quite the same again. His death would prove to have a profound impact on many lives, including mine.

Still today, words from Kuki Gallmann’s I Dreamed of Africa come to mind: ‘They had loved him, shared in fun, mischief, adventures. Now they shared the same anguish… contemplating their memories and their loss. This experience would forever live with them, and make them grow, and make them better, wiser.’

Even in death, Andy was still giving….

….This article also brings fond – and now also sad – memories of my friends John & Del Foster, who both died in older age in South Africa a few years ago now. And also of another special friend, Val De Montille (previous co-owner of Miombo Lodge, and then living in Brisbane, Australia) who died suddenly and unexpectedly late last year, aged just 61. My close friendship with Lol and Drew Searle, now based in the UK, still remains today…. My own health – suffering from some severe and extremely rare autoimmune conditions since fleeing Zimbabwe in 2014 (one of them a variation of Stiff Person Syndrome, which singer Celine Dion recently came out publicly saying that she has been devastated by) – means that I’m based back on the Sunshine Coast in Australia for regular hospital treatments, with my elephant awareness and conservation work now done from afar as I’m able. My last memoir titled ELEPHANT DAWN – which tells the story of all of my 13 years (and beyond) with the Hwange elephants, written without restraint after leaving the country – is available online in paper copy, ebook, audio book and CD.

Post published in: Environment

What a nice story it is my wish to work with her

Hi Ephraim, I’m no longer in Zimbabwe, but I hope you get your wish to work with wildlife.

So touching, now I feel like I also knew Andy🥲

Glad to know that even more people are becoming aware of Andy’s legacy. Thanks very much Keith.

Thanks so much to so many who read this via the link on my old http://www.facebook.com/PresidentialElephantsZim page – and also from the Rhodesians.Worldwide facebook page as well.

For those who are asking re other comment from me here, it’s this Rhodesians-Worldwide ‘public group’ facebook page, where you’ll find this post – https://www.facebook.com/groups/Rhodesians.Worldwide/?multi_permalinks=6429595457059061

Dear Sharon, I have just re-read your deeply moving tribute to Andy. Brings tears to my eyes and vivid memories back to my mind…. Not a day goes by that I don’t think of Andy. Not sure if you will see this? Wish we could see you again? But we are thinking of you and praying for you. God bless, Gordon and Debbie