BRENNA MATENDERE

In a briefing this past weekend after Mnangagwa’s shock appointment of Zimbabwe Defence Forces (ZDF) commander General Philip Valerio Sibanda as an ex-officio member of the ruling Zanu PF decision-making administrative party organ, politburo, security sources said the move signals yet another manoeuvre by the army which recently influenced the deployment of former ambassador to Tanzania retired Lieutenant-General Anselem Sanyatwe as the new Zimbabwe National Army (ZNA) commander.

Sanyatwe is a close ally of Vice-President Constantino Chiwenga, a retired general.

Although Sibanda is widely seen as Mnangagwa ally, he remains committed to the army project and on script to take over after the incumbent with his military allies.

He is earmarked to become vice-president under Chiwenga’s presidency.

Since the coup, Sibanda has been the stabilising factor for Mnangagwa.

In January 2019, he stopped Chiwenga from declaring a state of emergency and martial law during fuel price increase protests at a time when Mnangagwa was travelling in eastern Europe amid fears of yet another coup.

Sibanda did not think it was the right time for the army to step in, sources said.

The political war of attrition between Mnangagwa and Chiwenga most prominently found expression in the President’s controversial 2021 biography as internecine unresolved leadership issues linger on.

Former independent Norton MP Temba Mliswa previously said Mnangagwa’s former adviser Chris Mutsvangwa, now War Veterans minister, has been plotting to remove Chiwenga from his position.

Mutsvangwa was recorded by the late Zimbabwe National Army commander Lieutenant-General Edzai Chimonyo discussing the issue.

Mnangagwa and Chiwenga are fighting over the spoils of the November 2017 military coup.

Chiwenga, who engineered the coup and put Mnangagwa in power, thought the President would serve only one term and hand over the reins of power to him in 2023, but that has been publicly rejected, fuelling tensions and hostilities. Chiwenga feels betrayed.

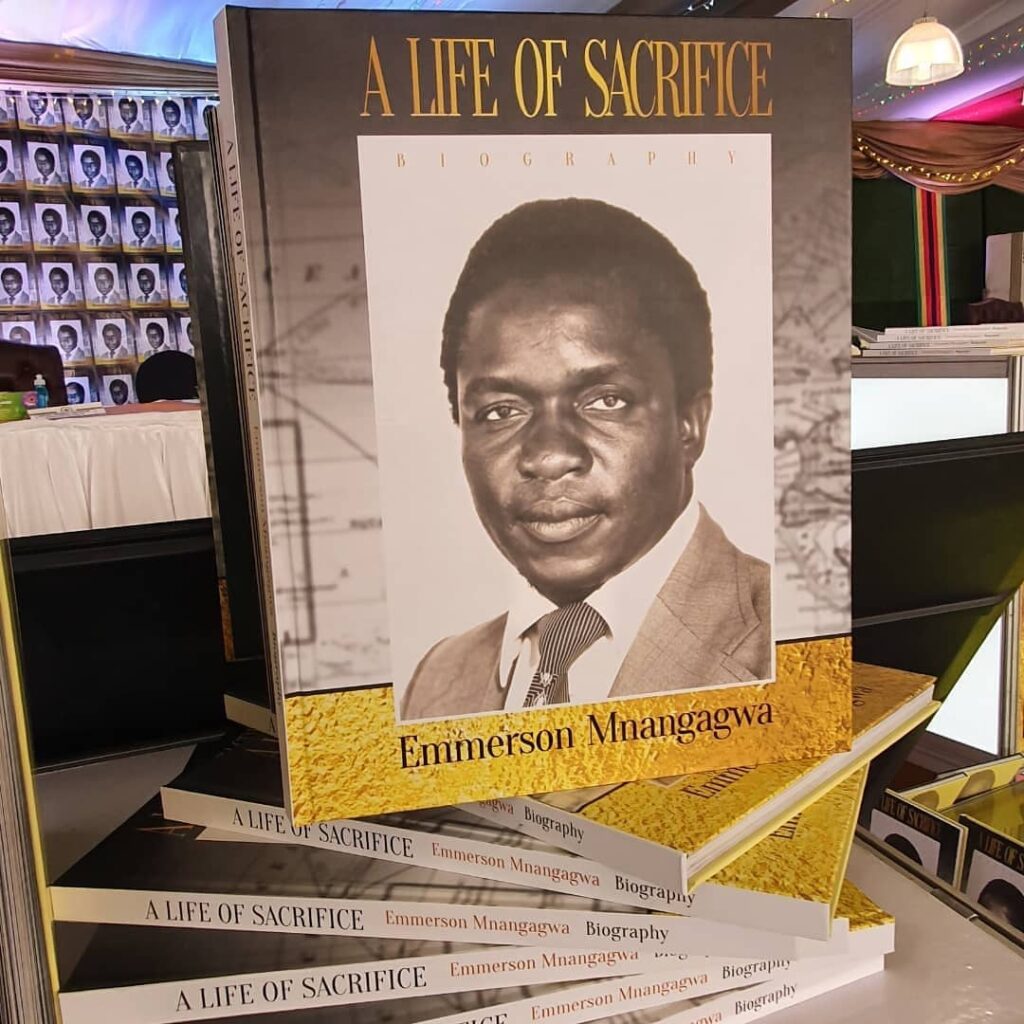

Mnangagwa’s authorised biography titled A Life of Sacrifice: Emmerson Mnangagwa exposes the rift between the two.

The 154-page biography, which Mnangagwa described as a “brief window” into his life, was authored by Eddie Cross, a former opposition MDC high-ranking official and MP who became the President’s adviser.

It depicts Chiwenga in negative light through its narrative.

Cross, Mnangagwa’s biographer and new loyalist, said the President will brook no nonsense from those threatening his hold on power, a warning to Chiwenga.

Mnangagwa, who at the time of the coup had fled the country to South Africa after his mentor-cum-tormentor Mugabe had hounded him, only returned after Chiwenga led the coup that ended the late dictator’s 37 years in power. Mugabe later described Mnangagwa as his “tormentor”.

The book reveals that Chiwengwa’s appointment as co-deputy, together with Kembo Mohadi, was part of Mnangagwa’s coup-proofing ploy.

Mnangagwa appointed Sibanda to succeed Chiwenga as ZDF commander as he saw him as loyal, although the army’s project remains intact.

Sibanda, according to the book, is “possibly the best soldier in southern Africa and a man that was deeply respected in the army”, which brings into focus Mnangagwa’s decision to appoint an ex-officio member of the politburo.

“Mnangagwa’s actions drew little attention, but what the President was doing was closing the door on any possibility of the military assisted transition (military coup) being repeated.

He needed to know that the security services were led by men in whom he had confidence as professionals,” the book says.

Differences between Mnangagwa and Chiwenga played out when the latter demanded that a state of emergency — martial law — be declared during the 2019 riots which had been triggered by a 150% increase in the price of fuel.

“When it became known that a state visit to Russia was planned for the week beginning the 14th January 2019, disturbing intelligence was received that disturbances were planned,” the book reads.

“The President consulted his security chiefs about the threat and gave instructions about what was to happen in his absence . . .”

The acting President retired General Chiwenga demanded that a state of emergency be declared and that Martial Law be introduced. This would have effectively meant that the armed forces took over the administration of the state and the commander-in-chief of security services, but General Sibanda refused. He said his orders from the President were very clear.”

This suggested a new rift between Chiwenga and Sibanda, although insiders say it was only a question of timing and strategy, not rivalry.

Internet services were suspended during the protests after security forces were deployed to quell the disturbances.

The coup deal between the coup-plotters was: Oust Mugabe, then install Mnangagwa and Chiwenga, the then ZDF commander, and Mohadi as co-vice-presidents.

Mnangagwa was to be the political and civilian face of the coup to avoid a backlash from the Southern African Development Community, African Union and the international community, including the United Nations.

Chiwenga was the military architect of the coup. He was at the centre of the planning and execution of the putsch, whose strong roots go back to 2008 when the army rescued Mugabe after he had lost to the late main opposition MDC-T leader Morgan Tsvangirai.

Mugabe told journalists in interviews in March 2018 at his Blue Roof Borrowdale mansion in Harare that Chiwenga was the architect.

Mnangagwa, with Chiwenga as the point man, engineered a contrived run-off between Mugabe and Tsvangirai when the opposition leader had actually won the presidential poll outright to save Mugabe. The MDC-T defeated Zanu PF by one parliamentary seat in the March 2008 elections.

Security sources say soon after the 2008 election fiasco for Mugabe and Zanu PF, and the army’s subsequent intervention, Mnangagwa and Chiwenga effectively took control.

After rescuing Mugabe, their only stumbling block was retired army commander General Solomon Mujuru who had managed to leverage his power and influence as a kingmaker to impose his wife Joice as vice-president at a Zanu PF congress at Sheraton Hotel (now Rainbow Towers) in Harare in December 2004.

This followed Mnangagwa’s Tsholotsho Declaration fiasco, which triggered purges within the party.

Mujuru and his faction defeated Mnangagwa’s group and took control in December 2004 after congress.

Their influence was hugely felt and manifested itself two years later at Zanu PF’s annual conference in Goromonzi in 2006 where leadership succession undertones were growing louder.

Things went off the rails in 2007 when Mujuru, strongly supported by the late Dumiso Dabengwa, forced an extraordinary congress in December 2007 ahead of the 2008 elections after a dispute over Mugabe’s candidature which played out in the politburo for months that year.

When Mugabe shrugged off Mujuru’s challenge in 2007, the former Zanla and ZNA commander plotted “bhora musango” (internal sabotage) — whose manifestation through centrifugal forces was the lead political actor Simba Makoni and his Dawn/Mavambo/Kusile project underwritten by Mujuru.

After the 2008 elections and the subsequent Government of National Unity which lasted from 2008 to 2013, Mujuru’s star started waning, although his wife remained vice-president.

Mujuru still remained a hindrance to Mnangagwa and Chiwenga’s coup project.

After heightened internal strife, Solomon Mujuru died in a mysterious fire on 15 August 2011.

Three years later, his wife Joice was kicked out as vice-president in a military operation executed through party structures in the form of recalls and dissolution of structures.

Mnangagwa came in to replace her. Phelekezela Mphoko was appointed by Mugabe another vice-president from nowhere in 2014 to replace John Nkomo who had died the previous year.

From 2014, Mnangagwa and Chiwenga started planning how to remove Mugabe as his succession battle intensified.

By 2016, Chiwenga was clear that a coup was necessary to remove Mugabe, security sources say.

Sources say Chiwenga even cited an attempted coup in Turkey at the time to explain what could happen in Zimbabwe.

On 15 July 2016, a faction within the Turkish Armed Forces, organised as the Peace at Home Council, attempted a coup against state institutions and government led by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

So Chiwenga’s role was central and critical in Mnangagwa’s ascendancy.

This explains why a deal had to be cut with Mnangagwa over the coup. Chiwenga was loyal and believed in Mnangagwa, who considers him a junior ally in terms of age and liberation struggle hierarchy, to leave power to him.

During his birthday celebrations in Harare last month, Mnangagwa thanked his wife Auxilia and Chiwenga for saving his life after he was poisoned in August 2017, indicating how loyal he was initially.

“I want my family to know that Chiwenga saved me,” Mnangagwa said during birthday celebration at State House.

Away from Chiwenga, Mohadi was political ally of the coup-plotters, representing Zapu in the anticipated new leadership matrix.

Sibanda was critical in the actual execution of the coup. At the time he was commander of the ZNA, which actually executed the putsch.

Without Sibanda’s cooperation, together with all the support of those below him like the retired Lieutenant-General Sibusiso Moyo, Major-General Trust Mugoba (also late) and retired Lieutenant-General Engelbert Rugeje and Sanyatwe, among others, the coup would not have taken place successfully.

Sibanda’s role in the coup was actually dramatised by Chiwenga at the ZDF commander’s mother Yowana Kubvoruno’s burial in Gokwe in July 2018.

At the burial, Chiwenga explained that Sibanda has actually provided an army force to escort Mnangagwa out of Zimbabwe through the Eastern Highlands after his dismissal as vice-president on 6 November 2017.

Mnangagwa escaped into Mozambique fearing arrest and poisoning by Mugabe and his allies.

He was taken from Beira in Mozambique to Pretoria, South Africa, by businessman Justice Maphosa who kept him at his house for at least two weeks as the coup was loading and during its execution.

When Mnangagwa returned home on 22 November 2017 — 16 days later — before he was sworn in as president two days later, Chiwenga and his military allies were sure that their 2023 deal with him was still intact.

However, no sooner had Mnangagwa taken office than cracks and tensions started appearing in the coup coalition.

A series of political activities widened the gulf between them as they started to fight over the coup spoils.

Mnangagwa entertained the idea of a government of national unity with the opposition MDC-T and Tsvangirai who had supported the coup.

He also wanted to bring in Dabengwa. Talks with these political actors, which the army opposed, collapsed.

Mnangagwa then tried to appoint Defence minister Oppah Muchinguri-Kashiri as vice-president, but the army blocked it.

That also applied to many other appointments at the time. Mnangagwa also forced to drop Mutsvangwa as minister and chief adviser as the army did not want him.

Chiwenga wielded veto power at the time.

Further, Mnangagwa tried to appoint Victor Matematanda as Zanu PF political commissar, but the army stopped him in his tracks and put Rugeje there.

After the 2018 elections, Mnangagwa — who was now relatively stronger after getting a public mandate to rule — removed Rugeje, a close Chiwenga ally, and put Matematanda.

Matematanda was later removed and posted to Mozambique as ambassador.

Rugeje was promised deployment to the Zimbabwe National Defence University as Vice-Chancellor. That did not happen. He is bitter about it.

Instead Rugeje’s house was attacked in October 2020 in what was said to have been an attempt to kill him, although the attack in which one person died was officially reported as robbery which occurred in his absence.

Sources say in December the same year, 2020, Rugeje was poisoned in Mutare and admitted to hospital during Zanu PF’s hotly contested district coordinating committee elections. The poisoning almost took his life, they say.

Besides when Rugeje was deployed to Zanu PF as political commissar in 2017, the army’s plan was to bring him back as ZDF commander to replace Sibanda who was earmarked to replace Mohadi under a Chiwenga presidency that was supposed to have begun in 2023 or after the recent elections.

Mnangagwa was expected to serve one term and leave this year, while Chiwenga took over.

However, Mnangagwa and his supporters showed Chiwenga and the army at the Zanu PF annual conference at Mzingwane High School in Esigodini in December 2018 that they were already working on his second term, six months into his first term.

That is the same way Mnangagwa and his allies behaved during the weekend at the Zanu PF annual conference in Gweru where their third-term political agenda became so clear.

Mnangagwa and Chiwenga’s rivalry was renewed after the recent elections as manoeuvres for a third term intensified.

Despite sugar-coated public speeches and acknowledgement of each other, Mnangagwa’s relations with Chiwenga were damaged beyond repair and irretrievably after the White City bombing incident in June 2018.

Insiders say Mnangagwa is convinced his colleagues, with military support, wanted to assassinate him. At the time, he said the attack was an inside job.

After that, Chiwenga suffered some mysterious illness and almost died. He was taken to South Africa, India and China for medication.

The Chinese saved his life. The story behind that has filtered through Chiwenga’s nasty divorce with his former wife Marry Mubaiwa.

The toxic marriage break-up was entangled in cut-throat power politics and Zanu PF’s unsettled leadership question.

Chiwenga and his allies say Mubaiwa was being used as a blunt political weapon by Mnangagwa’s henchmen against the vice-president, hence the vicious and tragic way she has been treated.

Due to the rivalry and tensions between Mnangagwa and Chiwenga, the former immobilised the military from running elections as they illegally had done mainly since 2000 at the height of the militarisation of politics in fear of bhora musango (internal sabotage) and replaced it with Forever Associates Zimbabwe (Faz), a Central Intelligence (CIO)-controlled hybrid securocratic entity that eventually ran the polls.

Mnangagwa’s surprise appointment Sanyatwe — Chiwenga’s closest military ally — as the new ZNA commander soon after the elections shows an attempt to realign the military amid army manoeuvres.

Sanyatwe replaced Lieutenant-General David Sigauke who retired recently. Sigauke had replaced the late Lieutenant-General Edzai Chimonyo in 2021. Before Sigauke came in, Mnangagwa and Chiwenga had fiercely fought over the proposed appointment of Rugeje as the ZNA commander.

Chiwenga wanted Rugeje, his close ally, to take charge, but Mnangagwa refused. A compromise was reached to place Sigauke in charge for two years. So the coming in of Sanyatwe signals a victory for the military over Mnangagwa’s politics.

The unexpected appointment of Sanyatwe with immediate effect is part of a major fightback campaign by the army which had been aggressively forced to retreat by Mnangagwa through a series of redeployments, purges, and mysterious deaths, according to informed military insiders.

Now Sibanda’s weekend appointment an ex-officio member of the Zanu PF politburo fits the army’s script from the beginning, despite complex dynamics and overlapping political power interests.

Chiwenga always envisaged Sibanda as his deputy after Mnangagwa representing Zapu since he was a Zipra commander, although he has no political base in Matabeleland region.

His other deputy was expected to come from Masvingo/Midlands (Rugeje) representing Karangas or retired Major-General Mike Nyambuya from Manicaland for Manyikas.

While Sibanda and Sanyatwe’s appointments — together with other changes coming — seem to be Mnangagwa’s power consolidation moves, they are actually military manoeuvres to retain control and go back to the original script of a Zimbabwe ruled by the military, sources say.