“If the water comes at all it’s often dirty,” Regai Chibanda, a 46-year-old father of five from the sprawling township of Chitungwiza, told me.

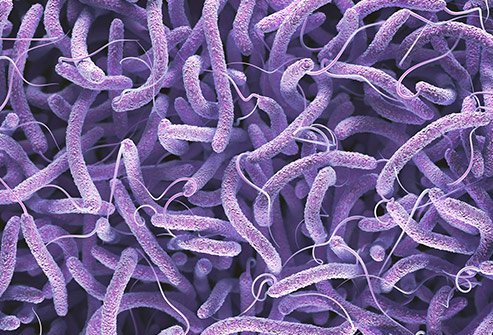

Cholera, an acute diarrheal infection caused by consuming food or water contaminated with the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, can spread quickly in cramped and dirty conditions.

It has become a kind of grim reaper to this southern African nation – back in 2008-2009 more than 4,000 went to their graves when the water-borne disease struck in what was already a frenzied and turbulent time.

Today inflation is again rearing its head and cholera has spread across all of the country’s 10 provinces, mainly affecting children, often left unsupervised in the stifling heat as their parents try to work.

This outbreak first struck back in February and as October ended official figures from the Health and Childcare Department are listing nearly 6,000 cases and some 123 suspected deaths.

President Emmerson Mnangagwa, who won disputed polls in August for a second term in office, has promised a nationwide borehole-drilling programme.

This is to be supported by solar-powered water points, mainly to serve some 35,000 villages which do not have access to clean drinking water.

In the capital, Harare, residents can go for weeks, or even months, without a regular supply of water from the Harare City Council. In Harare’s satellite township of Chitungwiza, more than 50 deaths were reported as October ended – all from cholera. (BBC)

Post published in: Featured