All sectors of society in Zimbabwe could not hold, the education system was in shambles, the social life was disintegrating and the economy was in tatters.

As a breadwinner for his extended family, which included his own children, his late brother’s children and his old mother including her other grandchildren, Ncube had to move to greener pastures.

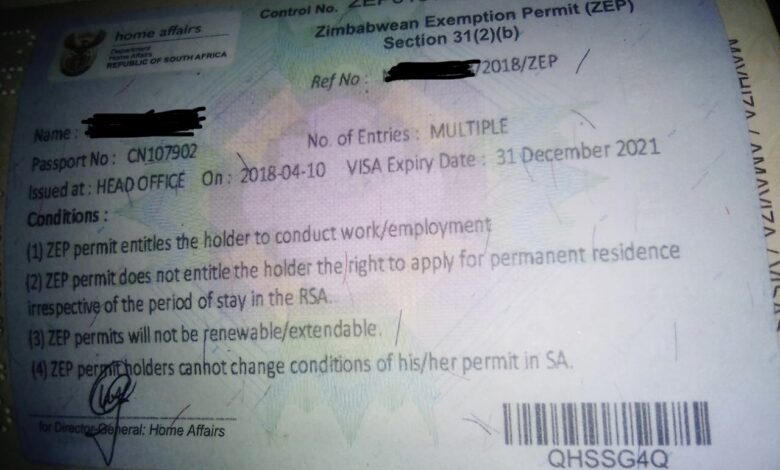

In South Africa, Ncube is one of the holders of the Zimbabwe Exemption Permits (ZEPs), negotiated between the Zimbabwean immigrants, the Zimbabwean government and the then Minister of Home Affairs, Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma.

When Ncube arrived in South Africa, he managed to find a teaching job in one of the many private schools in central Johannesburg.

Even though the job is poorly-paying in terms of the standards in South Africa, it is better than what he left behind in Zimbabwe.

He could manage to put together some money and send groceries home every month-end through omalayitsha, the cross-border couriers between South Africa and Zimbabwean cities and districts.

However, Ncube faces a headache as the year – 2022 enters the second half.

As the year slowly trudges on to its end, his stay in South Africa under the ZEP permit is slowly coming to an end.

In 2009, the South African government introduced a Dispensation of Zimbabwean Permit (DZP) to legalise the many Zimbabweans already inside the country because of the political and socio-economic situation in Zimbabwe.

The government of South Africa encouraged Zimbabweans who until then had applied for asylum to apply for a DZP and about 295 000 people applied for the permit.

Just over 245 000 permits were issued, with the balance being denied due to lack of passports or non-fulfilment of other requirements.

The permits were valid for four years.

In 2014, the DZP was renamed the Zimbabwe Special Permit (ZSP); and then in 2017 renamed the ZEP.

About 182 000 Zimbabweans applied for the ZEP permit when the application process started on 15 September 2017.

These permits expired on 31 December 2021.

The government of South Africa last year refused to renew the ZEP permits and announced that Zimbabweans on that facility should move to other permits available within the laws of the country or leave the country at the end of this year.

In his prose piece, No Man is an Island, the English poet John Donne, ends with the powerful words: “Never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.”

This line means people should feel a sense of belonging to the whole of the human race, and should feel a sense of loss at every death, because it has taken something away from mankind.

In that sense, as the days march towards the end of the year, the bell of the end of the termination of ZEPs tolls, not only for the holders of the permits, but a large number of people, especially their families back home.

Chairperson of the Zimbabwe Community in South Africa, Ngqabutho Nicholas Mabhena, said the organisation is working hard to make sure that the South African government reverses its decision otherwise there will be a crisis.

“It is correct that the majority of the ZEP holders are breadwinners back in Zimbabwe,” he said.

“This is going to create a crisis as their income is going to be affected. This means that from January 2023, if they are not able to move to other visas, it’s going to be a crisis. People will not be able to support their families as they are likely to lose their jobs. This is why as the Zimbabwe Community in South Africa, working with the African Diaspora Forum, we call on the South African government to review its decision because this is going to create a crisis.”

He added, “It is not only the holders of the ZEP that are going to be affected but also their families back in Zimbabwe.”

If the ZEPs are cancelled and somehow, Zimbabweans manage to hold on to their jobs, that means their income would be diminished as employers will find them an easy target for exploitation.

One of the issues raised by the Put South Africa First movement is that employees prefer to take on undocumented migrants whom they can pay low salaries.

Ayana Moyo from rural Matabeleland North in Zimbabwe says she fears that if her permit is not renewed, she will struggle to make ends meet.

“I have two children back in Zimbabwe living with my old mother,” she said.

“Every month I have to send food and other groceries. My mother is ill and cannot do much for their upkeep. I have to take care of all that. She is looking after eight children including my sisters’ children.

“I also have to send school fees and other costs related to their education. Some of my sisters are late, which means that me and my other sister, also here in South Africa, have to look after these children.”

African Diaspora Global Network leader, Dr Vusumuzi Sibanda, stated there is a likelihood that over a million people are “going to starve” as a result of the withdrawal of the ZEP permits.

“The broader implications of the withdrawal of the ZEP, especially on those that are working and using the ZEP, is that they will not be able to send their children to school,” he said.

“Most of them have support of an average of six members per family, with four children at most, plus a mother and father, making them six.

“This means that all of them will ultimately end up with no form of support. Children will drop out from school and a lot of them will not have jobs to get to when they get back to Zimbabwe. If they remain here, they lose their jobs as well as become illegal. So, it’s a very serious situation because, if you multiply by almost 200 000, you are looking at about over a million people that are going to starve as a result of the situation we are faced with.”

Moyo works as a domestic worker in one of the affluent suburbs of Johannesburg.

“Although my salary is not much, I have the advantage of being a live-in domestic worker,” she said. “That means I have no accommodation costs.”

Thembelihle Dube from rural Matabeleland South said after the permits expire, he is not planning on going back home at all.

“I have no job in Zimbabwe at all and going back will mean that I will starve together with my family that depends on me,” he said.

“I have been here in South Africa for almost 15 years now. The ZEP and earlier permits were introduced while I had already started working here in this country.

“I have invested many years of my life here. It was not easy at the beginning, especially before the permits. The expiry of these permits will inconvenience me. However, I don’t see myself going back home. I will revert to the survival strategies that I used before the permits were introduced. It will not be easy. The stakes will be high. It would mean low paying jobs, paying bribes to police and other people, and more importantly hiding from the Dudula people.”

The Helen Suzman Foundation (HSF) is challenging the termination of the permits in court as the decision would leave many people desperate and vulnerable.

According to the Foundation, permit holders “will be put to a desperate choice: to remain in South Africa as undocumented migrants with all the vulnerability that attaches to such status or return to a Zimbabwe that, to all intents and purposes, is unchanged from the country they fled.

“There are thousands of children who have been born in South Africa to ZEP holders during this time who have never even visited their parents’ country of origin.”

In his response to the court action, South Africa’s Minister of Home Affairs, Aaron Motsoaledi, accused the Foundation of playing a “destructive role” in relation to South Africa’s democracy.

“The Minister of Home Affairs has always engaged the HSF regarding some of the challenges faced by the Department in the past,” he said.

“The Minister has engaged with HSF on several occasions with positive outcomes.”

The minister also told the media in South Africa that the Foundation was engaging in propaganda.

“This is their (HSF) take when they want to run propaganda,” he told Newsroom Africa.

“When we took this decision (to terminate ZEPs), we actually issued directives for people who want clarity.”

Civil society organisations in the country have since encouraged the minister to withdraw the statement and apologies to the Foundation.

As the possible end of the permits is paralleled by a rise in the anti-Zimbabwe xenophobia sentiments, the Zimbabwe Community in South Africa chairperson said this is likely to affect many migrants as well.

“We have seen the rise of narrow nationalism in the world, in general, particularly after the rise of Donald Trump in the US,” Mabhena said.

“Here in South Africa, we saw the emergence of Herman Mashaba with his worrying conduct especially when he became the Johannesburg mayor and later when he formed his own political party, ActionSA.

“We also saw the emergence of other right wing political parties who have won some seats especially in the Johannesburg city council. We have seen the emergence of populist movements like Operation Dudula and Put South Africa First and others that are raising or campaigning on the anti-migrant ticket.

“This is expected to increase as we go to the 2024 elections. The migration question will continue to be at the centre of electoral politics. At this stage the attack is on Zimbabweans and we have said assuming that Zimbabweans were to leave, they will go to another migrant community. This is worrying.

“It is also affecting those that are documented because these right-wing formations cannot differentiate between the person who is documented and the person who is not documented. The inspections that they are carrying out in removing people, especially hawkers, have shown that clearly. This might extend to other cities. We saw it happening in Durban sometime.”

this is not going to affect zimbabweans only even south africans most house owners will be without rental income hundreds of thousands of bank account will be closed the local economy of south africa will be heavily affected it means less customers less demand less jobs for the locals